| Sea Ice Ends Year at Same Level as 1979

|

|

Daily

Tech | January 1, 2009

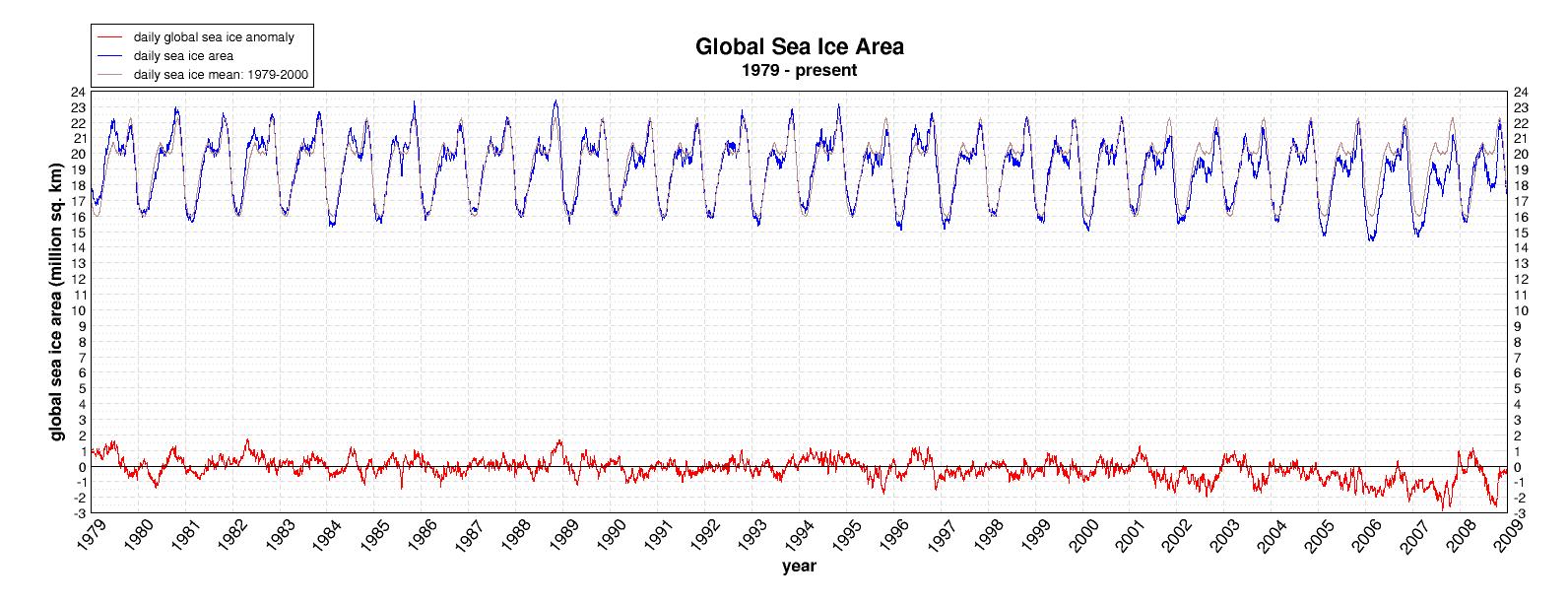

Rapid growth spurt leaves amount of ice at levels seen 29 years ago. Thanks to a rapid rebound in recent months, global sea ice levels now

equal those seen 29 years ago, when the year 1979 also drew to a close. |

|

| Ice levels had been tracking lower throughout much of 2008,

but rapidly recovered in the last quarter. In fact, the rate of increase

from September onward is the fastest rate of change on record, either upwards

or downwards.

The data is being reported by the University of Illinois's Arctic Climate Research Center, and is derived from satellite observations of the Northern and Southern hemisphere polar regions. Each year, millions of square kilometers of sea ice melt and refreeze. However, the mean ice anomaly -- defined as the seasonally-adjusted difference between the current value and the average from 1979-2000, varies much more slowly. That anomaly now stands at just under zero, a value identical to one recorded at the end of 1979, the year satellite record-keeping began. Sea ice is floating and, unlike the massive ice sheets anchored to bedrock in Greenland and Antarctica, doesn't affect ocean levels. However, due to its transient nature, sea ice responds much faster to changes in temperature or precipitation and is therefore a useful barometer of changing conditions. Earlier this year, predictions were rife that the North Pole could melt entirely in 2008. Instead, the Arctic ice saw a substantial recovery. Bill Chapman, a researcher with the UIUC's Arctic Center, tells DailyTech this was due in part to colder temperatures in the region. Chapman says wind patterns have also been weaker this year. Strong winds can slow ice formation as well as forcing ice into warmer waters where it will melt. Why were predictions so wrong? Researchers had expected the newer sea ice, which is thinner, to be less resilient and melt easier. Instead, the thinner ice had less snow cover to insulate it from the bitterly cold air, and therefore grew much faster than expected, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center. In May, concerns over disappearing sea ice led the U.S. to officially list the polar bear a threatened species, over objections from experts who claimed the animal's numbers were increasing. |

|